Aug. 2, 2021

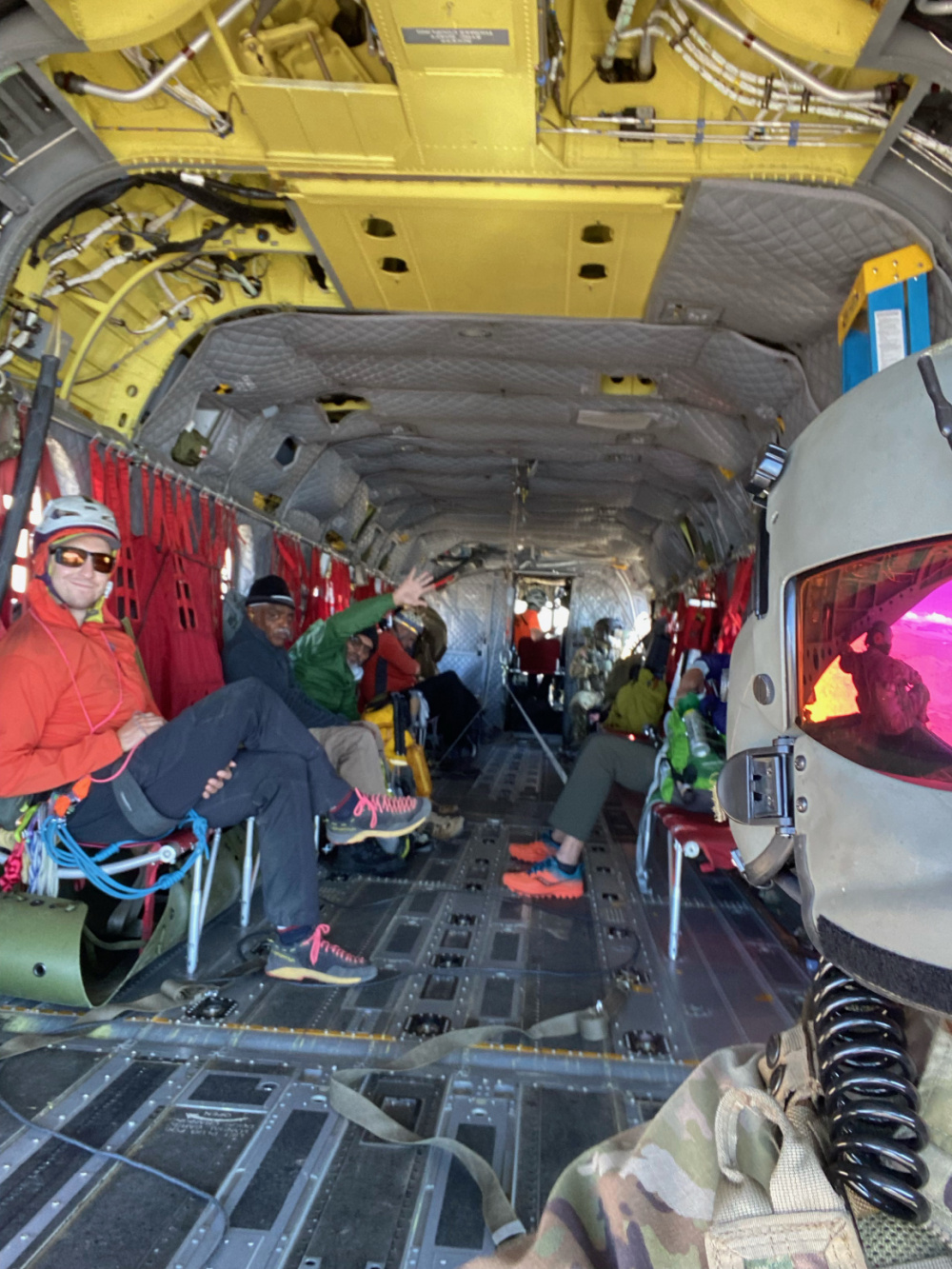

SACRAMENTO, Calif. – Three hikers who spent the night stranded on Mt. Whitney with limited supplies in cold weather were taken to safety by a California Army National Guard aircrew, July 29, during a mission to support the Inyo County Sheriff’s Office via the California Governor’s Office of Emergency Services.

U.S. Army Chief Warrant Officer 3 Aaron Mello and four crew members took off Tuesday morning in a CH-47 Chinook helicopter from Cal Guard’s Army Aviation Support Facility in Stockton and headed toward the highest mountain peak in the contiguous United States.

“The clouds were pushed up against the mountain, so we couldn’t just go straight up the valley to them,” Mello said. “We had to go around, pop over the top and come back in the valley from the backside.”

They popped out above 13,500 feet.

The high altitude required supplemental oxygen for the crew and placed additional challenges on flight conditions.

“The air gets pretty thin,” Mello said.

The aircraft circled a few times before finding the hikers near the final camp of the mountain’s 14,505 ft. summit.

“The people we were looking for were ambulatory, not very well, but other hikers were helping them,” he said.

He and the crew looked for a place to land the helicopter, but a flat spot sixty feet long was nowhere in sight.

“We hovered around a little bit because we just could not find a place to put the aircraft,” Mello said. “It was real rocky, real steep and uneven.”

The crew had two options: drop off a search and rescue team that would help the already exasperated hikers get to a better landing zone somewhere down the mountain – which would add extra physical demands on the rescuees and delay their evacuation by at least an hour or more – or perform a riskier two-wheeled landing to get the stranded hikers off the mountain quickly.

“We said, ‘look, if they’re moving around under their own power there’s people down there assisting them, let’s just put it down here and drop the ramp,'” Mello said. “We’re here, we can do it, let’s pull them out now and get them back down the mountain as soon as we can.”

To perform what’s known as a pinnacle landing, the crew looked for a 20 ft. by 20 ft. rock shelf large enough to land the helicopter’s back wheels and far enough from the mountainside to keep from hitting the six rotor blades.

It’s a move they practice often, Mello said, just in case they have to do it during a real-world scenario.

“We played that game of precise positioning for a couple minutes to even find a spot where we could safely get both wheels on the ground without a rock punching a hole in the aircraft or popping a tire,” Mello said.

While Mello and fellow pilot Chief Warrant Officer 3 Craig Hannon worked the flight controls, the flight engineer and two crew chiefs kept eyes on the blade clearance and coached the pilots where to move the back end of the helicopter in order to stick the landing.

“Without our flight engineer and crew chiefs, we couldn’t do it,” Mello said.

“When I look out my window, all I see is a big valley beneath my feet. The ground is a couple hundred feet below me,” he said. “I can’t see what I’m landing on in the back, so I’m just following their cues and holding the aircraft as still and as steady as I can.”

Staff Sgt. George Esquivel, the crew’s flight engineer, laid off the edge of the helicopter’s back ramp to call for positioning as wheels lowered onto a slightly sloped rock. Once down, however, the aircraft started to roll and the crew had to abort the landing attempt.

Sgt. Kyle Reeves, one of the two crew chiefs, spotted a flatter rock about 25 ft. away on his side of the aircraft, while Spc. Julian Lopez kept an eye out for rotor blade clearance.

“From the pilot’s perspective, he’s backing up blind,” said Reeves. “There is no backup camera or anything. We are the backup camera.”

Reeves hung out of the cabin door and called for positioning in five foot and then one foot increments as cross-winds continued to blow against the Chinook.

“The aircraft still wanted to go down the hill, so I had to put one of the tires in a small dimple that was in the rock,” Reeves said.

With Reeves’ guidance, Mello nestled one tire into a stone indentation roughly the size of a basketball. The dimple provided enough grip to keep both tires on the cliff face, Reeves said.

“They’re my eyes in the back,” Mello said. “You have to trust them completely.”

For the next three-to-five minutes, with the back half of the helicopter landed with the ramp down and the front half still flying, Mello and Hannon fought to keep helicopter perfectly stable while crew movement in the back of the aircraft changed its center of gravity and 30-knot wind gusts tried to blow the helicopter off its position.

“When you’re on the pinnacle, you’re working really hard to not let the wind shove you off when it gusts,” Mello said. “Every limb you have is gainfully employed in making small adjustments to keep you where you need to be. It’s like riding a unicycle and trying to juggle.”

With the nearly 25,000 lb. helicopter’s open ramp as a pivot point, any movement of the back end could injure or crush the other crew members, the on-board search and rescue team, or the hikers being rescued, he said.

“Once you think you’re stable, and you say, ‘okay, I’m stable, lower the ramp and start the rescue effort,’ you are undeniably committed until it’s over,” Mello said.

Once both back wheels were down, Esquivel knew they were fighting the clock to get the hikers on board the aircraft.

“The second we were able to land, we had very limited time,” Esquivel said. “Our pilot on the controls was fighting all the terrain, the wind, and rotor wash. We wanted to make sure he was comfortable the whole time during that situation, so we just sped up the process as much as we could.”

The hikers “looked very tired and withered,” Esquivel said, but they were able to move without limping and did not appear restricted in their walking.

“We kind of rushed them to the aircraft,” he said, knowing how precarious the situation was. “Everybody’s safety came into consideration.”

With the hikers, the search and rescue team and helicopter’s crew members all safely back on board, Mello and Hannon lifted off the mountainside and headed to Bishop Airport in the Owens Valley where they dropped off the team and hikers before returning to Stockton.

Mello credits their continual training and crew communication for the mission’s success, but says the best part of the rescue was the rescue itself.

“It feels great to rescue people who are alive,” he said.

Reeves agreed.

“When we get to come in and make a major rescue like this for people who need it, it’s a good day.”